Why don’t adults always do exactly what we feel like doing, when we feel like doing it?

This is a question that you might hear from kids, and it perfectly encapsulates what baffles them about adults.

As adults, we pretty much have free rein to do whatever we want, whenever we want. The vast majority of us won’t get arrested for not showing up to work, and no one will haul us off to prison for eating cake for breakfast.

So, why do we show up for work? Why don’t we eat cake for breakfast?

Perhaps the better question is, how do we keep ourselves from shirking work when we don’t want to go? How do we refrain from eating cake for breakfast and eating healthy, less-delicious food instead?

The answer is self-regulation. It’s a vital skill, but it’s also something we generally do without much thought.

If you want to learn more about what self-regulation is, how we make the decisions we make, and why we are more susceptible to temptation at certain moments, read on. We also provide plenty of resources for teaching self-regulation skills to both children and adults.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Self-Compassion Exercises for free. These detailed, science-based exercises will not only help you increase the compassion and kindness you show yourself but will also give you the tools to help your clients, students, or employees show more compassion to themselves.

Andrea Bell from GoodTherapy.org has a straightforward definition of self-regulation: It’s “control [of oneself] by oneself” (2016).

Self-control can be used by a wide range of organisms and organizations, but for our purposes, we’ll focus on the psychological concept of self-regulation.

As Bell also notes:

“Someone who has good emotional self-regulation has the ability to keep their emotions in check. They can resist impulsive behaviors that might worsen their situation, and they can cheer themselves up when they’re feeling down. They have a flexible range of emotional and behavioral responses that are well matched to the demands of their environment”

The goal of most types of therapy is to improve an individual’s ability to self-regulate and to gain (or regain) a sense of control over one’s behavior and life. Psychologists might be referring to one of two things when they use the term “self-regulation”: behavioral self-regulation or emotional self-regulation. We’ll explore the difference between the two below.

Behavioral self-regulation is “the ability to act in your long-term best interest, consistent with your deepest values” (Stosny, 2011). It is what allows us to feel one way but act another.

If you’ve ever dreaded getting up and going to work in the morning but convinced yourself to do it anyway after remembering your goals (e.g., a raise, a promotion) or your basic needs (e.g., food, shelter), you displayed effective behavioral self-regulation.

On the other hand, emotional self-regulation involves control of—or, at least, influence over—your emotions.

If you had ever talked yourself out of a bad mood or calmed yourself down when you were angry, you were displaying effective emotional self-regulation.

Self-regulation theory (SRT) simply outlines the process and components involved when we decide what to think, feel, say, and do. It is particularly salient in the context of making a healthy choice when we have a strong desire to do the opposite (e.g., refraining from eating an entire pizza just because it tastes good).

According to modern SRT expert Roy Baumeister, there are four components involved (2007):

These four components interact to determine our self-regulatory activity at any given moment. According to SRT, our behavior is determined by our personal standards of good behavior, our motivation to meet those standards, the degree to which we are consciously aware of our circumstances and our actions, and the extent of our willpower to resist temptations and choose the best path.

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you to help others create a kinder and more nurturing relationship with themselves.

Download PDF

By filling out your name and email address below.

According to Albert Bandura, an expert on self-efficacy and a leading researcher of SRT, self-regulation is a continuously active process in which we:

Bandura also notes that self-efficacy plays a significant role in this process, exerting its influence on our thoughts, feelings, motivations, and actions.

A quick thought experiment can show the significance of self-efficacy:

Imagine two people who are highly motivated to lose weight. They are both actively monitoring their food intake and their exercise, and they have specific, measurable goals that they have set for themselves.

One of them has high self-efficacy and believes he can lose weight if he puts in the effort to do so. The other has low self-efficacy and feels that there’s no way he can hold to his prescribed weight loss plan.

Who do you think will be better able to say no to second helpings and decadent desserts? Which of them do you think will be more successful in getting up early to exercise each morning?

We can say with reasonable certainty that the man with higher self-efficacy is likely to be more effective, even if both men start with the exact same standards, motivation, monitoring, and willpower.

Barry Zimmerman, another big name in SRT research, put forth his own theory founded on self-regulation: self-regulated learning theory.

Self-regulated learning (SRL) refers to the process a student engages in when she takes responsibility for her own learning and applies herself to academic success (Zimmerman, 2002).

This process happens in three steps:

When students take initiative and regulate their own learning, they gain deeper insights into how they learn, what works best for them, and, ultimately, they perform at a higher level. This improvement springs from the many opportunities to learn during each phase:

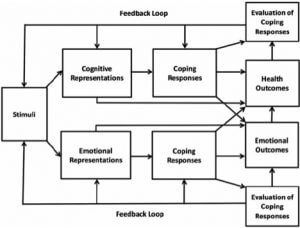

It can be useful to consider the self-regulatory model to better understand SRT.

While the model is specific to health- and illness-related (rather than emotional) self-regulation, it is still a good representation of the complex processes at work during self-regulation of any kind.

The figure to the right shows how the model works:

If words like “stimuli” and “emotional representations” throw you off, perhaps an example of the model in action will help.

Let’s use Bob as our example.

Bob was just diagnosed with diabetes and is facing his new reality: having to check his blood sugar regularly, changing his diet, and getting comfortable with needles. The diagnosis is Bob’s stimulus.

Bob attempts to make sense of his diagnosis. He talks to his doctor, recalls a friend’s experience with diabetes, thinks about a character’s struggle with diabetes on his favorite TV show, and tries to remember what he learned about diabetes in his college health classes. All of this information feeds into his cognitive representation of his diagnosis.

It’s not all objective thoughts, though. Bob also feels a little shocked about getting this diagnosis since he hadn’t even considered that he might have diabetes. He is worried about how long he’ll be around for his kids and is anxious about how much his life will change. He’s also scared about what will happen if he doesn’t change his life. These feelings make up his emotional representation of his diagnosis.

Once Bob has a semi-firm grasp of his thoughts and feelings about the diagnosis, he makes some decisions about what comes next. Through discussions with his doctor, he decides to start a new, healthier diet and commits to taking frequent walks. However, he also finds that it’s easy to put his diagnosis out of his mind when he’s not having an episode or being directly affected by it.

These decisions and actions are his coping responses.

Bob implements these responses for a few days, then reflects on how he’s been doing. He realizes that, although he is eating marginally healthier and he’s taken a short walk each day, he has mostly refrained from thinking about his diagnosis at all.

Bob reminds himself that if he keeps ignoring his diabetes, he will eventually get sick and may even suffer significant, long-term consequences. This is his evaluation of his representations and coping methods.

Bob commits to facing his diabetes head-on instead of denying it and resolves to work on remembering the potential consequences of not staying healthy. He also resolves to embrace fully the diet he and his doctor planned out and to start going to the gym three times a week.

Bob is using his evaluation of his representations, coping responses, and outcomes to assess how well his actions align with his desired future: a happy and healthy Bob who is around to see his kids grow up. This is the feedback loop.

This example is a good representation of what self-regulation looks like. Essentially, it’s the process of monitoring your own thoughts, feelings, and behaviors; comparing the outcomes against your goals; then deciding whether to maintain your current attitudes and behaviors or to adjust them in order to meet your goals more effectively.

As noted earlier, you could argue that all forms of therapy are centered on self-regulation—they all aim to help clients reach levels of equilibrium in which they are able to effectively regulate their own emotions and behaviors (and, sometimes, thought patterns, in the case of therapies like cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy).

However, there is also a form of therapy that is specifically designed with self-regulation theory and its principles in mind. Self-regulation therapy draws from research findings in neuroscience and biology to help clients reduce “excess activation in the nervous system” (Canadian Foundation for Trauma Research & Education, n.d.).

This excess activation (i.e., an off-balance or inappropriate fight-or-flight response) can be triggered by a traumatic incident or any life event that is significant or overwhelming.

Self-regulation therapy aims to help the client correct this problem, building new pathways in the brain that allow for more flexibility and more appropriate emotional and behavioral responses. The ultimate goal is to turn emotional and/or behavioral dysregulation into effective self-regulation.

If you’re thinking that self-regulation and self-control have an awful lot in common, you’re correct. They are similar concepts and they deal with some of the same processes. However, they are two distinct constructs.

As psychologist Stuart Shanker (2016) put it:

“Self-control is about inhibiting strong impulses; self-regulation [is about] reducing the frequency and intensity of strong impulses by managing stress-load and recovery. In fact, self-regulation is what makes self-control possible, or, in many cases, unnecessary.”

Viewed in this light, we can think about self-regulation as a more automatic and subconscious process (unless the individual determines to purposefully monitor or alter his or her self-regulation), while self-control is a set of active and purposeful decisions and behaviors.

An important SRT concept is that of self-regulatory depletion, also called ego depletion.

This is a state in which an individual’s willpower and control over self-regulation processes have been used up, and the energy earmarked for inhibiting impulses has been expended. It often results in poor decision-making and performance (Baumeister, 2014).

When a person has been faced with many temptations (especially strong temptations), he or she must exert an equally powerful amount of energy when it comes to controlling impulses. SRT argues that people have a limited amount of energy for this purpose, and once it’s gone, two things happen:

This is a key idea in SRT. It explains why we struggle to avoid engaging in “bad behavior” when we are tempted by it over a long period of time. For example, it explains why many dieters can keep to their strict diet all day but once dinner’s over they will give in when tempted by dessert.

It also explains why a married or otherwise committed person can rebuff an advance from someone who is not their partner for days or weeks but might eventually give in and have an affair.

Recent neuroscience research supports this idea of self-regulatory depletion. A study from 2013 by Wagner and colleagues used functional neuroimaging to show that people who had depleted their self-regulatory energy experienced less connectivity between the regions of the brain involved in self-control and rewards.

In other words, their brains were less accommodating in helping them resist temptation after sustained self-regulatory activity.

Although self-regulatory depletion is a difficult hurdle, SRT does not imply that it is impossible to remain in control of your urges and behavior when your energy is depleted. It merely states that it becomes harder and harder as your energy level decreases.

However, there are many examples of successful self-regulatory behavior, even when the individual is fatigued from constant self-regulation.

As you can see, self-regulation covers a wide range of behaviors from the minute-to-minute choices to the larger, more significant decisions that can have a significant impact on whether we meet our goals.

Let’s take a closer look at how self-regulation helps us in enhancing and maintaining a healthy sense of wellbeing.

Overall, there’s tons of evidence suggesting that those who successfully display self-regulation in their everyday behavior enjoy greater wellbeing. Researchers Skowron, Holmes, and Sabatelli (2003) found that greater self-regulation was positively correlated with wellbeing for both men and women.

The findings are similar in studies of young people. A study from 2016 showed that adolescents who regularly engage in self-regulatory behavior report greater wellbeing than their peers, including enhanced life satisfaction, perceived social support, and positive affect (i.e., good feelings) (Verzeletti, Zammuner, Galli, Agnoli, & Duregger).

On the other hand, those who suppressed their feelings instead of addressing them head-on experienced lower wellbeing, including greater loneliness, more negative affect (i.e., bad feelings), and worse psychological health overall (Verzeletti, Zammuner, Galli, Agnoli, & Duregger, 2016).

To get more specific, one of the ways in which self-regulation contributes to wellbeing is through emotional intelligence.

Emotional intelligence can be described as:

“The ability to perceive emotions, to access and generate emotions so as to assist thought, to understand emotions and emotional knowledge, and to reflectively regulate emotions so as to promote emotional and intellectual growth”

(Mayer & Salovey, 1997).

According to emotional intelligence expert Daniel Goleman, there are five components of emotional intelligence:

Self-regulation, or the extent of an individual’s ability to influence or control his or her own emotions and impulses, is a vital piece of emotional intelligence, and it’s easy to see why: Can you imagine someone with high levels of self-awareness, intrinsic motivation, empathy, and social skills who inexplicably has little to no control over his or her own impulses and is driven by uninhibited emotion?

There’s something off about that picture because of self-regulation’s important role in emotional intelligence. And, as researchers Di Fabio and Kenny found, emotional intelligence is strongly related to wellbeing (2016).

The better we are at understanding and addressing our emotions and the emotions of others, the better we are at making sense of our environments, adjusting to them, and pursuing our goals.

Speaking of pursuing our goals, self-regulation is also entwined with motivation. As stated earlier in this article, motivation is one of the core components of self-regulation; it is one factor that determines how well we are able to regulate our emotions and behaviors.

An individual’s level of motivation to succeed in his endeavors is directly related to his performance. Even if he has the best of intentions, well-laid plans, and extraordinary willpower, he will likely fail if he is not motivated to regulate his behavior and avoid the temptation to slack off or set his goals aside for another day.

The more motivated we are to achieve our goals, the more capable we are to strive toward them. This impacts our wellbeing by filling us with a sense of purpose, competence, and self-esteem, especially when we are able to meet our goals.

As you might have guessed, self-regulation is also an important topic for those struggling with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

One of the hallmarks of ADHD is a limited ability to focus and regulate one’s attention. For example, ADDitude’s Penny Williams (n.d.) describes her 11-year-old son Ricochet’s struggles with ADHD in terms of the struggle to self-regulate:

“At times, he has struggled with identifying his feelings. He is overwhelmed with emotion sometimes, and he has trouble labeling his feelings. You can’t deal with what you can’t define, so this often creates a troublesome situation for him and me. Now that Ricochet is old enough to start regulating his reactions, one of our current behavior goals is identifying, communicating, and regulating feelings and actions.”

Similarly, difficulty with emotional self-regulation is part and parcel of ASD. Those on the autism spectrum often have trouble identifying their emotions. Even if they are able to identify their emotions, they generally have trouble modulating or regulating their emotions.

Difficulty with self-regulation is well-understood as a common symptom of ASD, but effective methods for improving self-regulation in ASD is unfortunately not as well-known or regularly implemented as one might wish.

The nonprofit advocacy group Autism Speaks suggests several strategies for helping children with autism to learn how to self-regulate. Many of these strategies can also be applied to children with ADHD, including:

Helping your child learn to self-regulate more effectively will ultimately benefit you, your child, and everyone he or she interacts with and will improve his or her overall wellbeing.

Mindfulness can be defined as the conscious effort to maintain a moment-to-moment awareness of what’s going on, both inside your head and around you. Mindfulness and self-regulation are a powerful combination for contributing to wellbeing.

As we learned earlier, self-regulation requires self-awareness and monitoring of one’s own emotional state and responses to stimuli. Being conscious of your own thoughts, feelings, and behavior is the foundation of self-regulation: Without it, there is no ability to reflect or choose a different path.

Teaching mindfulness is a great way to improve one’s ability to self-regulate and to enhance overall well-being. Mindfulness encourages active awareness of one’s own thoughts and feelings and promotes conscious decisions about how to behave over simply going along with whatever your feelings tell you.

There is good evidence that mindfulness is an effective tool for teaching self-regulation. Researchers Razza, Bergen-Cico, and Raymond recently published a study on the effects of mindfulness-based yoga intervention in preschool children (2015).

The researchers found that those in the mindfulness group exhibited greater attention, better ability to delay gratification and more effective inhibitory control than those in the control group.

Findings also suggested that those with the most trouble self-regulating benefited the most from the mindfulness intervention, indicating that those at the lower end of the self-regulation continuum are not a “lost cause.”

Mindfulness is an excellent way to build certain attention skills, which are part of a larger set of vital skills that allow us to plan, focus, remember important things, and multitask more effectively.

These skills are known as executive function skills, and they involve three key types of brain functions:

These skills are not inherent but are learned and built over time. They are vital skills for navigating the world and they contribute to good decisionmaking.

When we are able to successfully navigate the world and make good choices, we set ourselves up to meet our goals and enjoy greater wellbeing.

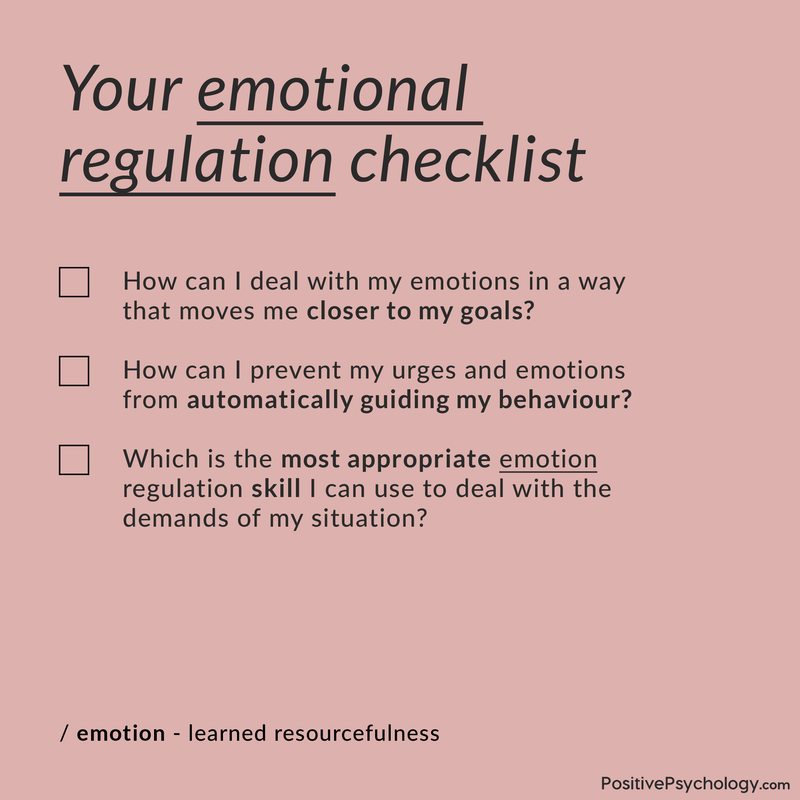

emotion regulation checklistDo you ever find your emotions frustrating, overwhelming, or even rather unbearable? Are you able to cultivate an awareness of these emotions but aren’t really sure what to do next?

After noticing and understanding your emotions, it is important to think about how to deal with or regulate these emotions. There are many ways to do this, but a good place to start is to consider asking yourself the questions in the images below.

The more you challenge yourself to answer these important questions and try out other emotional regulation strategies, the more resources you’ll have to process your emotions effectively. This idea has been termed “learned resourcefulness”.

Research shows people who have learned to be resourceful in this way, have a more diverse range of emotional-regulation strategies in their toolkit to deal with difficult emotions and have learned to consider the demands of a difficult situation before selecting an appropriate strategy.

Importantly, these strategies are equally relevant when attempting to regulate positive emotions like happiness, excitement, and optimism. One may engage in techniques to prolong positive emotions in an attempt to feel better for longer or even inspire motivation and other adaptive behaviors.

If you’re interested in measuring your level of self-regulation (or using it in research), there are two solid options in terms of a self-monitoring scale and self-regulation questionnaire:

The SRQ is a 63-item assessment measured on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The items correspond to one of seven components:

If you’re interested in learning more about this scale or using it in your own work, visit this website.

If you’re more interested in working with young children on self-regulatory strategies, the PRSA will probably work best for you. It’s described as a portable direct assessment of self-regulation in young children based on a set of structured tasks, including activities like:

To learn more about this assessment or to inquire about using it for your research, click here.

As noted earlier, the development of self-regulation begins very early on. As soon as children are able to access working memory, exhibit mental flexibility, and control their behavior, you can get started with helping them develop self-regulation.

So, you’re probably convinced that self-regulation in children is a good thing, but you might be wondering, Where do I begin?

If that captures your thought process, don’t worry. We have some tips and suggestions to get you started.

Here’s a good list of suggestions from Day2Day Parenting for supporting the self-regulation of very young children (e.g., toddlers and preschoolers):

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises, activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!”

— Emiliya Zhivotovskaya, Flourishing Center CEO

You can also use games and activities to help young children build their self-regulation skills.

Check out the resources listed below for some fun and creative ideas for kindergarten and preschool children.

We titled these the “classic games” because they are popular, well-known games that you are probably already familiar with. Luckily, they can also be used to help your child develop self-regulation.

If you haven’t already, give these a try:

Some further suggestions come from the Your Therapy Source website (2017):

Another list from The Inspired Treehouse includes good suggestions for other games you can play to calm an emotional or overwhelmed child when you’re on an outing. You can find that list here.

As your child grows, you will probably find it harder to encourage continuing self-regulation skills. However, adolescence is a vital time for further development of these skills, particularly for:

To ensure that you are supporting adolescents in developing these vital skills, there are three important steps you can take:

This leads to an important point: Children reach another significant stage of self-regulation development when they begin attending school—and self-regulation is tested as school gets more challenging.

This is where Zimmerman’s self-regulated learning theory comes into play again. Recall that there are three times when self-regulation can aid the learning process:

Zimmerman encourages teachers to do the following three things to help students continue to develop self-regulation:

If you’re a teacher who is interested in implementing more techniques and strategies for encouraging self-regulation in your classroom, consider the resources and methods outlined below.

This resource from McGill University in Canada includes several helpful lesson plans for building self-regulatory skills in students, including lessons on:

The self-regulation lesson plans from the College & Career Competency Framework detail nine separate lessons you can use to help your students continue to develop their skills. The lessons range in length from about 20 to 40 minutes and can be modified or adapted as needed.

The lessons include:

Click here to access and purchase the workbook containing the lessons. It includes the information you need to build effective strategies into your curriculum.

Finally, for a treasure trove of lesson plans, activities, and readings you can implement in your classroom, click here.

This resource comes from Scott Carchedi at the School Social Work Network, and includes a student manual and four lesson plans:

For each lesson, you can access a lesson plan and student activity (or activities) via a Word document and a student reading via a PDF. Use these lessons to help your students boost their self-regulation skill development and adapt or modify them as needed.

Although much attention is paid to self-regulation in children and adolescents because that’s when those skills are developing, it’s also important to keep self-regulation in mind for adults.

For example, self-regulation is extremely important in the workplace. It’s what keeps you from yelling at your boss when he’s getting on your nerves, slapping a coworker who threw you under the bus, or from engaging in more benign but still socially unacceptable behaviors like falling asleep at your desk or stealing someone’s lunch from the office fridge.

Those with high self-regulation skills are better able to navigate the workplace, which means they are better equipped to obtain and keep jobs and generally outperform their less-regulated peers.

To help you effectively manage your emotions at work (and build them up outside of work as well), try these tips:

These tips likely come off as very general, but it’s true that living a generally healthy life is key to reducing your stress and reserving your energy for self-regulation.

For more specific tips on building your self-regulation skills, read on.

There are many tips you can use to enhance your self-regulation skills. If you want to give it a shot, read through these techniques and pick one that resonates with you—then try it out.

Cultivating the skill of mindfulness will improve your ability to maintain your moment-to-moment awareness, which in turn helps you delay gratification and manage your emotions.

Research has shown that mindfulness is very effective at boosting one’s conscious control over attention, helping people regulate negative emotions, and improving executive functioning (Cundic, 2018).

This strategy can be described as a conscious effort to change your thought patterns. This is one of the main goals of cognitive-based therapies (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy or mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy).

To build your cognitive reappraisal skills, you will need to work on changing and reframing your thoughts when you encounter a difficult situation. Adopting a more adaptive perspective to your situation will help you find a silver lining and help you manage emotion regulation and keep negative emotions at bay (Cundic, 2018).

Cognitive self-regulation has also been found to be positively correlated with social functioning. It involves the cognitive abilities we use to integrate different learning processes, which also help us support our personal goals.

This list comes from the Mind Tools website but can also be found in this PDF from Course Hero. It outlines eight methods and strategies for building self-regulation:

This table from Jan Johnson at Learning in Action Technologies lists 23 strategies we can use to self-regulate, both as an individual and as someone in a relationship.

The strategies are categorized into two groups: “Positive or Neutral” and “Negative or Neutral.” Check out some examples in each column and think about where your most frequently used self-regulating learning strategies fall on the chart.

For example, in the upper-left quadrant (“Alone Focus, Positive or Neutral”), strategies include:

Under the “Relationship—Focus on Other, Positive or Neutral” category, strategies include:

Finally, the strategies under the “Relationship – Focus on Self, Positive or Neutral” category include:

To see the rest of these strategies, click here (Clicking the link will trigger a download of the PDF).

If you’re a teacher, parent, or adult who works with children, this section offers some great resources for helping you and/or the children in your care develop greater self-regulation.

This worksheet is a handy tool that teachers can implement in the classroom. It can be used to help students assess their levels of self-regulation and find areas for improvement.

It lists 23 traits and tendencies that the students can say they do “Always,” “Sometimes,” or “Not So Much.” For the full list, you can see the worksheet here, but below are some examples:

This handout can be useful for both adults and older children and teens. It describes some of the main strategies and skills you can implement to keep emotions under control.

The handout covers four main strategies:

You can download this handout here.

Help your clients develop a kinder, more accepting relationship with themselves using these 17 Self-Compassion Exercises [PDF] that promote self-care and self-compassion.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

If you’re still hungry for more information on self-regulation, there are tons of resources available on the subject. Check out the sources listed below.

Aside from the worksheets and handouts noted earlier, there are another handy tool to use with kids: the self-regulation chart.

This self-regulation chart is for parents and/or teachers to complete, but it is focused on the child. It lists 30 skills related to emotional regulation and instructs the adult to rate the child’s performance in each area on a four-point scale that ranges from “Almost Always” to “Almost Never.”

All of these skills are important to keep in mind, but the skills specific to self-regulation include:

You can find the self-regulation chart and checklist at this link.

If you spend some time poking exploring self-regulation literature or talking to others about the topic, you’re bound to run into mentions of The Zones of Regulation.

According to developer Leah Kuypers, The Zones of Regulation is a “systematic, cognitive-behavioral approach used to teach self-regulation by categorizing all the different ways we feel and states of alertness we experience into four concrete colored zones” (Kuypers, n.d.).

This book describes the Zones of Regulation curriculum, including lessons and activities you can use in the classroom, in your therapy office, or at home.

In this book, you will learn about the four zones:

In addition, reading the book will teach you how to apply the Zones model to help your children, students, or clients build their emotional regulation skills.

You can learn more about this book here.

For a more academic look at self-regulation, you might want to give this handbook a try.

This volume from researchers Kathleen D. Vohs and Roy F. Baumeister offers a comprehensive look at the theory of self-regulation, the research behind it, and the ways it can be applied to improve quality of life. It also explains how self-regulation is developed and shaped by experiences, and how it both influences and is influenced by social relationships.

Chapters on self-dysregulation (e.g., addiction, overeating, compulsive spending, ADHD) explore what happens when self-regulation skills are not developed to an adequate level.

If you’re a student, researcher, academic, a helping professional, or an aspiring helping professional, you won’t regret investing your time and energy into reading this book and familiarizing yourself with this important topic.

Click here to see the book on Amazon.

The skills involved in self-regulation are necessary for achieving success in life and reaching our most important goals. These skills can also have a major impact on overall wellbeing.

Self-regulation is truly an important topic for everyone to consider. However, it might be even more important for parents and educators to learn about it, since it is an important skill for children to develop.

What do you think of self-regulation theory? What are your strategies for boosting your own self-regulation? What about your strategies for building it in children?

Let us know in the comments section below. If you want to learn more about a similar topic, try reading this piece on positive mindsets.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Self Compassion Exercises for free.

References